Criticism on an altar and spitting on a painting: the contemporary art of Gallarate has always astounded

In 1953, the objections to "picassian" art were much more radical than the comments on social networks about the new altar in “Santa Maria Assunta”. This was only one of the episodes regarding contemporary art (from sculpture to architecture, to theatre) that has found fertile ground in the town.

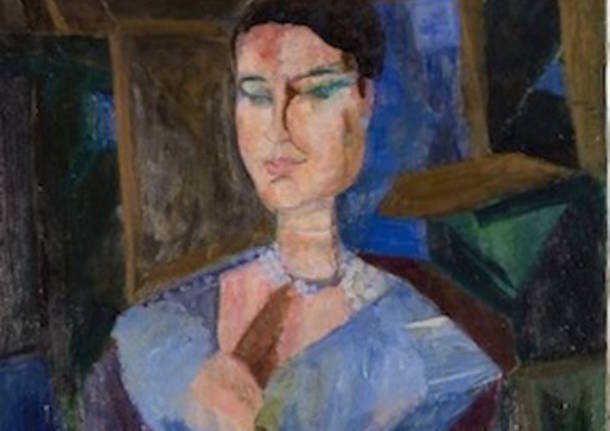

It was 1953, the Gallarate Visual Arts Award was won by “Woman in Purple” by Bruno Cassinari. This “vaguely Picasso-like work” caused a scandal.

“Some right-minded people got very angry about it; some, many, spat at it,” said Giovanni Orsini, who today is the Chairman of the Gallarate Award. “I can still remember Professor Zanella cleaning it in the evening. And yet, other much more challenging works were not so vehemently challenged.” (Click here, for information about “Woman in Purple”, on the website of the MAGA).

This is the Gallarate of contemporary art, a town that has succeeded in being provocative, conflictual and stimulating, from the end of the Second World War onwards, to the new altar in the Basilica, a work by Claudio Parmiggiani, which has rekindled the discussion, with hundreds of comments on social media, including qualified comments, favourable and critical, also by those who followed the work from start to finish. It has been referred to as an “altar of severed heads” in some newspapers, and (keeping only to the newspapers) the work has also earned ample space in more important publications, including La Repubblica and Corriere, Avvenire, and the publications of anti-modernist and pre-conciliar Catholicism.

“Sacred art has aroused a lot of objections, from Giotto to the nudity of Michelangelo, to the works of Caravaggio; the Dominicans replaced one with Carracci instead; in Rome, they objected to the Vocation of Saint Matthew, which depicts the Saint with dirty feet,” said Giovanni Orsini. Returning to the case of the altar in Gallarate, he said, “It would have been absurd if no one had spoken about it: before, the altar was ignored, anyone who entered only looked up at the architecture. Today, it’s become central, and its classic style recalls that of the neoclassical church.”

When it comes to visual art, Gallarate’s Visual Arts Award was crucial in defining the role of the town, which has risen above the sleepy province to earn space and a reputation. Of course, it is not the great workshop that Milan is, but it has been acknowledged a certain role, at least in the province, with a definition of Little Athens, which it earned at a time when everything else around was interested only in “making money, to make money, to make money”.

There was no shortage of objections, also to the Gallarate Award, not only to “Woman in Purple”, but also to other works, sometimes for cost reasons. “I remember the criticisms over the purchase of Emilio Vedova’s futuristic work; we had bought it for ITL 2000, the same price as Carrà’s View of Santa Maria del Fiore. The former was criticised, the latter was not. Today, the Carrà is worth €50,000, the Vedova, over €300,000.”

When we talk about a town, we talk about many different subjects. The public administration, the municipality, but also the church, private clients. So, in architecture, we can mention the audacity of Giulio Minoletti’s Casa del Fascio: this rationalist monolith, which was built in 1940, when the war had already begun, with its forms seemed to anticipate the passing of Fascism and its pompous rhetoric of Ancient Rome. Unlike the more traditional Casa del Balilla by Paolo Mezzanotte, which is now a library, the Casa del Fascio still causes heated discussion, despite its being forgotten by the public authority (after a phase of partial restoration inside, there are no other plans to restore it).

And, moving on to private construction, consider the how much astonishment caused, at the beginning of the 1970s, by Carlo Moretti’s “Camma condominium”, between Via XX Settembre and Piazzetta Guenzati. This unusual inclusion in the heart of the old village, which looked like a house of the future, rejected the traditional forms, introduced aerial passages and glass galleries, with a bold use of cement. And it still overcame the distinction between public and private space, with its pedestrian passage “full of metropolitan grandeur”. Almost half a century later, it is still futuristic. Or at least futuristic as they saw it then, technological, revolutionary, detached from the past.

And if a private building could cause controversy, what of a monument, which, by definition, is a public, collective statement. There was a great deal of astonishment (and lively debate) over the new monument to the Resistance, designed by Arnaldo Pomodoro, which was inaugurated in 1980. Professor Zanella contacted more than two hundred artists, galleries and critics, and selected works by Andrea Cascella, Pietro Consagra, Fausto Melotti, Floriano Bodini, Marcello Morandini and Vittorio Tavernari. And in the end, the committee chose Pomodoro’s “Movimento di Crollo”, a broken monolith that went entirely beyond the figurative representation of the Resistance; it was revolutionary, in so far as it projected the anti-fascist heritage entirely into the contemporary world, beyond reducism. It caused discussion, but it made a strong mark on the urban landscape, inserted between distinctly modern styles of architecture.

And contemporary elements can also be seen in sacred art, not only today with the altar. One example is the Church of San Paolo in Sciarè, which was designed in the early 1970s by the architects Maria Rosa Zibetti Ribaldone and Benvenuto Villa. Their building recalled the shapes of a ship, went beyond the idea of aisles and, by placing the faithful around the altar, reflected the dictates of the Second Vatican Council, while the absence of fences eliminated any separation from the surrounding town. At the time, objection was more ideological. “On the day of the consecration, with Cardinal Colombo, the parish priest Don Guglielmo found the church covered with red paint, with the words ‘More houses, fewer churches; no to the masters’ pyramids’,” Giovanni Orsini remembers.

Today, the church in Sciarè is presided over by Don Alberto Dell’Orto, the great promoter of the “Delle Arti” Theatre, who, in the mid-1970s, had the audacity to bring Dario Fo, who, by reinterpreting the “tradition of medieval jesters”, was revolutionary in the theatre. The “Delle Arti” was, and still is, a parish theatre, an almost unique example of being open to experimentation; another chapter in the workshop that is Gallarate.

Roberto Morandi

TAG ARTICOLO

La community di VareseNews

Loro ne fanno già parte

Ultimi commenti

flyman su Ilaria Salis candidata alle europee con Alleanza Verdi Sinistra nel collegio NordOvest

Alberto Gelosia su Ilaria Salis candidata alle europee con Alleanza Verdi Sinistra nel collegio NordOvest

lenny54 su I no vax sono tornati a colpire in provincia: imbrattati i muri della redazione di Varesenews

malauros su I no vax sono tornati a colpire in provincia: imbrattati i muri della redazione di Varesenews

Felice su I no vax sono tornati a colpire in provincia: imbrattati i muri della redazione di Varesenews

PaoloFilterfree su A Varese Salvini prova a ricucire passato e futuro della Lega, ma Bossi non c'è

Accedi o registrati per commentare questo articolo.

L'email è richiesta ma non verrà mostrata ai visitatori. Il contenuto di questo commento esprime il pensiero dell'autore e non rappresenta la linea editoriale di VareseNews.it, che rimane autonoma e indipendente. I messaggi inclusi nei commenti non sono testi giornalistici, ma post inviati dai singoli lettori che possono essere automaticamente pubblicati senza filtro preventivo. I commenti che includano uno o più link a siti esterni verranno rimossi in automatico dal sistema.